Description

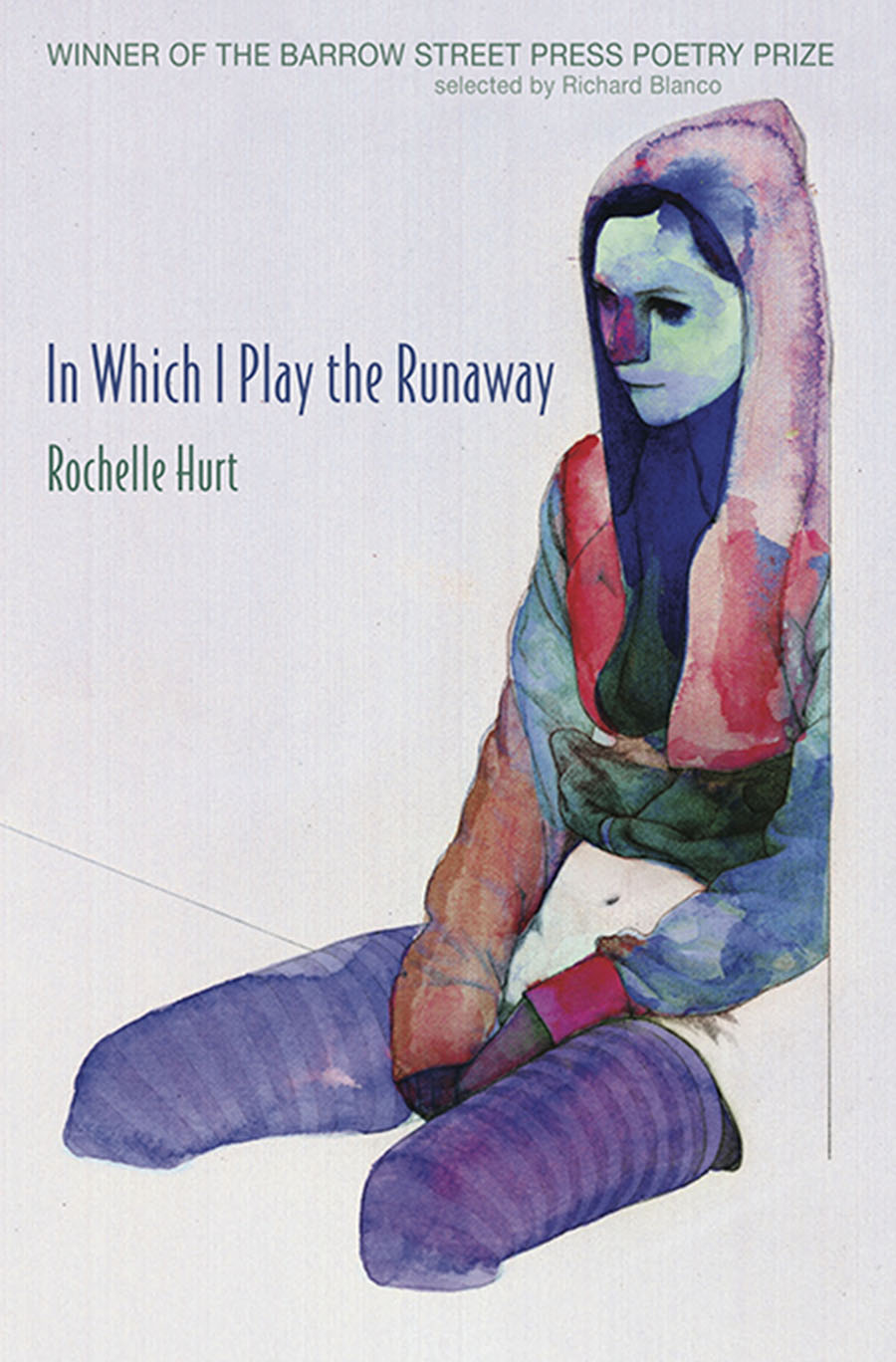

Barrow Street 2015 Prize Winner

“I was born with a gift for gall and grit,” Rochelle Hurt writes—a line that echoes through every poem in this collection. She spares nothing and bares all that needs baring about family, place, and relationships—how they reflect each other, blurred in tarnished mirrors. With a Sylvia Plath-like abandon and urgency, every single word feels completely necessary; words spoken with a vigor and honesty that are felt in the gut; words that remain lodged in the back of the throat.

—Richard Blanco, Contest Judge

Textured with the silt of a river that has never been itself twice, In Which I Play the Runaway gifts us the voice of a poet who is not only willing but determined to trouble the conventions of two-dimensional portraiture. Here, fables and futures, memory and mythology, and objects and subjects flicker out of their assigned places in the diorama’s mirror so that we might re-imagine the transformative possibilities of a sense of place: “home is a bullet” the I “swallows again and again,” and from an empty grave, a girl will wake “not saved… but changed.” With a great intentionality of formal range and a voice that haunts its world with its clear minerality and purpose, Hurt insists on the irreducibility of the daughters, wives, women, and girls who find any concept of home in this book, in which “all the women I’ve been… have never ceased / to believe they exist.” We are lucky to have this book in the world.

—Lo Kwa Mei-en

In her new poetry collection, In Which I Play the Runaway, Rochelle Hurt rewrites everything previously said about place. It’s as if Hurt took a map of America, redrew all the state lines, and saved only the best city names: Aimwell, Nightmute, Neverstill, Honesty. Then she filled those towns with tough beauty and longing, everyday objects and encounters acquiring new weight in a landscape that aches like home while also striking us with its singularity. “As expected, after the wedding, the house / became a cough we lived in, trembling / in the throat of that asthmatic spring,” begins the poem “Self-Portrait in Needmore, Indiana,” which goes on to show us, “The streets stacked and curved like fingers / on a grease-knuckled hand gripping / the waist of our Midwestern dream.” This is an unforgettable book, a vital and compelling voice.

—Mary Bidding

“It was the year of miracles/piling up inside you, tiny/and black as chokeberries.” Tweet

“In this way, I was forever/the runaway, indolent trinket of his.” Tweet

Poem in Which I Play the Runaway

It could open with a party, strewn

with girls like tinsel, girls looking

for a house to stuff themselves in,

girls with two parents, girls glaring

with the joy of needlessness.

Or a chase scene: some ranch house

with walls thin as a mother’s dress,

long emptied of men and closing on me.

I never wanted a home in him,

but the sex was like licking sheets

of corrugated iron, my torn maw

breathing in the corrosion. The scent

of him alone was like coming

home to a father’s midnight grip.

In this way, I was forever

the runaway, indolent trinket of his.

But if you want it, I’ll give

the story of a woman’s deboning

by a pair of junk-rutted hands,

her good marrow honed to a prick

on a promise like a diamond file.

And how she loved it, the sin itself

a new kind of homelessness.

Diorama of a Fire

In the living room, evidence

of accident: glue dropped

on the floor, welling with the glare

of the steel nail scissors, giant

beside the candy box sofa. See, propped

on top, two horse-haired dolls.

See their fixed elbows, greased with heat. See,

stuffed in this one’s hand, a linen scrap—

my sister dabbing at my knee, stirring

the gravel trapped beneath

the plastic flap of sallow skin.

What care,

to weave these bits of glass and rock

and grass into the flesh of the knee.

Left of the paper partition a moth lies

folded—my mother—soot shoulders

curled, face taut as she falls

infinitely further inward

and her shoebox house coughs up gray bolls

of cotton, pasted to the walls around her.

But the spark is further back.

I sift

the stack of cut-out colors—the black

chain of smoke, the orange match head,

the brown shred of flooring—and find

at my fingers another white rag, paper

edges scalloped, cloud-round.

I remember

it into the cardboard kitchen, where it sits

stoveside, doused in peroxide, dripping.

Now watch: I am a godhand

pulling loose threads from the curtains,

testing the corners with breath.